Risks of Falling Behind

The system the U.S. Department of Defense uses to buy technology, installed in 1983-1984, has been viewed as a problem for years. As the supporting bureaucracy has grown, the system has become increasingly inefficient and burdensome, leading to numerous failed attempts to replace it. It has also long been a popular punching bag in the media, with references to the $640 toilet seat and other more recent examples of waste.The problem is becoming worse, and more dangerous for national security. We have moved beyond a system that inefficiently allocates resources to one that is structurally unable to keep up with the increasing pace of technological advancement. In war, being a generation of technology behind your opponent often means that you will lose, potentially in a disastrous fashion, as the Iraqi military experienced in 1991. The technological margins that separate life from death in war are razor thin.

Generations in military technology used to be measured in decades. That time is shrinking, as technology is evolving faster and faster in all domains. In some hardware domains, the generational cycle is as short as 18-36 months. For software, that cycle can be as short as days or weeks.

The U.S. Defense Acquisition process is designed for 10+-year cycles to develop, prototype, and field new equipment. The average major defense acquisition program (MDAP) that reported between 1997-2015 took around 7 years from initiation to initial operational capability (IOC at Milestone B or C for those who speak the parlance). When we add 2-5 years of technology development, proposals, and contract negotiations on the front end of this 7-year timeframe and often several years from IOC to full operational capability (FOC) on the back end, we often exceed 10 years.

The Joint Strike Fighter, for example, is expected to reach IOC for the Navy in 2019, 18 years after Lockheed Martin was awarded the contract and 23 years after the program began.

There is an existential disconnect between a 10+-year buying cycle and an 18-month innovation cycle. This is a national security issue that will cost American lives in the horrifying and hopefully unlikely event that there is another great power war that involves the U.S. My sincere hope is that this will never happen, but a cursory review of human history leads me to believe that betting against a future great power conflict is a high-risk bet.

It is important that we understand that the conditions have changed since we wrote the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) in 1983. It should come as no surprise that a process and bureaucracy created before the digital revolution is no longer applicable in the age of smartphones, AI, autonomous vehicles, and gene editing. American power and innovation have created a technological advantage that has served as a cushion, allowing this issue to continue to be kicked down the road. However, this cushion is shrinking, and will soon be gone.

The pace of innovation is not likely to slow down. If anything, it will speed up. This requires an enduring, structural fix (or outright replacement) of the system the U.S. uses to buy defense technology.

Money is Not the Problem

Money is not the problem, and more money is not the solution. More money may be needed to continue to fight the nation's wars, but it is unclear that any reasonable amount of additional top-line DoD funding will alleviate the structural issues of the defense acquisition system. The process of spending money to buy technology needs to be better aligned with technology development cycles.The defense budget has experienced significant growth since 2001. According to the SIPRI database, the rolling 5-year average for annual military expenditures in constant 2015 dollars was around $400 billion in 2000. By 2005 expenditures had reached $600 billion, which seems to constitute a new floor for defense spending. Expenditures peaked at $759 billion in 2010, and have averaged $664 billion from 2005-2016.

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), available here.

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2015, the Department of Defense obligated $274 billion in current dollars on federal contracts, which was greater than all other federal agencies combined. The percentage of spending on R&D is also decreasing, from 18% of total contract obligations in FY 1998 to 9% in FY 2015.

This is not a criticism. We have had the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other regions to pay for, and the 2016 expenditure level of $606 billion represents a historically reasonable 3.3% of GDP. However, it is interesting to note that the armed forces have roughly the same number of uniformed service members and similar air- and land-based platforms as in 2001. There was not a 50% increase in military personnel or systems to accompany the increase in the budget. There has been innovation, to be certain: new aircraft such as the F35, new avionics variants of old helicopters such as the UH60M, and many other great innovations. But in general the defense apparatus simply costs more than it used to. A wartime military does and should costs more, as there are inevitable increases for direct war costs, realistic training, more competitive pay, and better facilities.

The point is that the money is there, and past performance shows us that adding a few extra hundred billion to the defense budget on a sustained basis has not resulted in dramatically new tools to increase the performance of Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines in combat. There does not seem to be a direct correlation between top-line spending and transformative technology-enabled outcomes. The challenge is more complex than one that could be solved by simply throwing money at it.

What the FAR Produces

The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) is a 1,933 page document that governs the acquisition process by which the executive agencies of the United States buy goods and services. The Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) is a 1,462 page document that provides additional Department of Defense-specific guidance for buying goods and services. Additionally, the Department of Defense Instruction 5000.02 (DODI 5000.02) provides policies and procedures for the implementation of the defense acquisition system.These documents grew from humble beginnings. The FAR is the implementation of both a 1979 statute to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) “promoting the development and implementation of uniform procurement system,” and the Competition in Contracting Act (CICA) of 1984, which was passed as part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984. The CICA repealed the Armed Forces Procurement Act of 1947, which was the prior statute governing the process for buying military goods and services.

The CICA legislation’s stated intent was to decrease costs, increase competition, and allow more small businesses to win federal government contracts. This was the origin of the “full and open competition” mandate that is commonly referenced today. The CICA and resulting FAR included a number of provisions around procurement announcements, contract award standards, and protest procedures that provide the core of the current manifestation of the FAR and DFARS, along with their supporting bureaucracies.

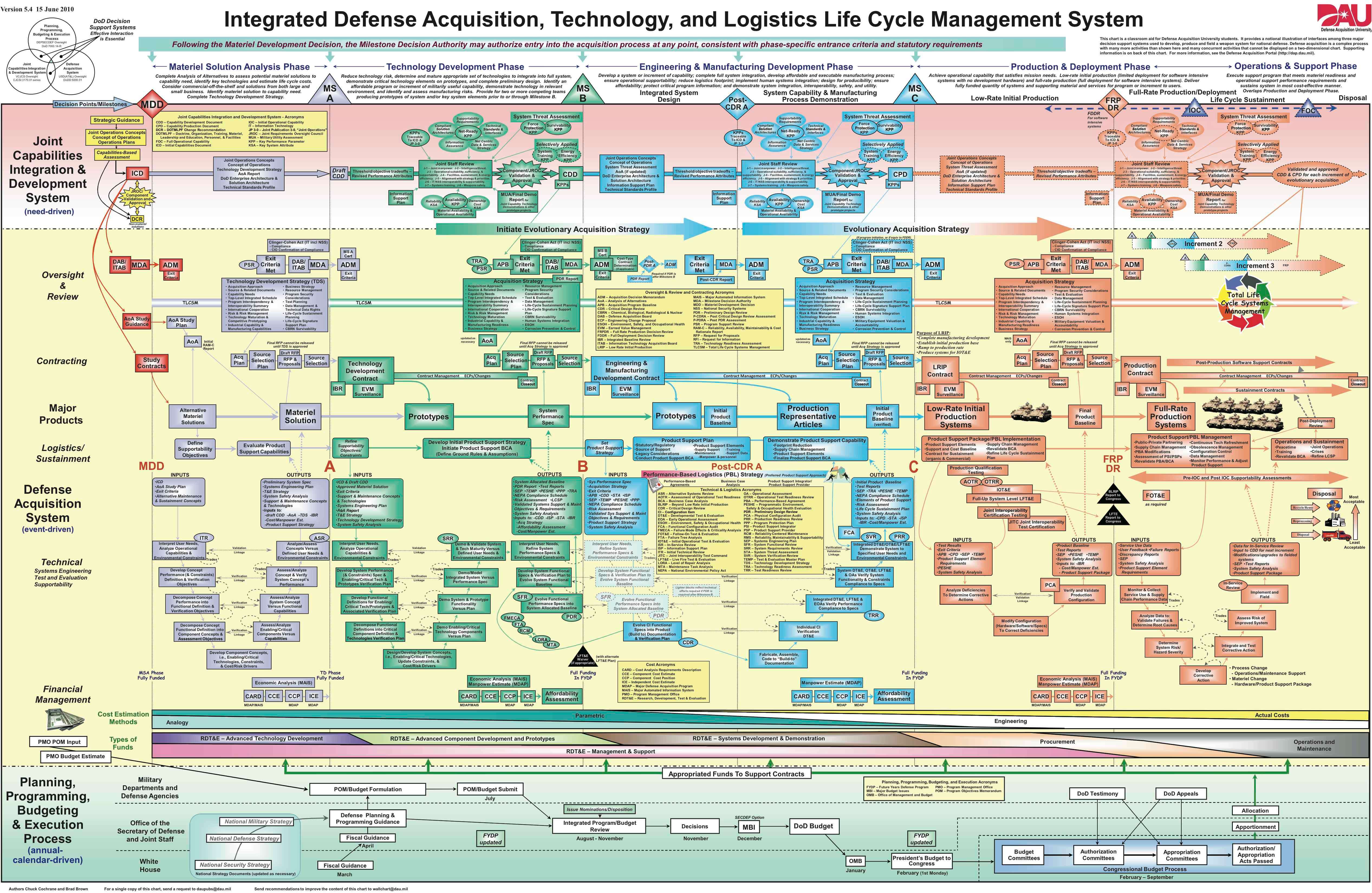

Those bureaucracies are not small -- the Department of Defense alone has around 156,000 civilian and military employees in its acquisition workforce. The eye chart below depicts the end-to-end process that these 156,000 individuals manage, a process of breathtaking complexity.

Source: Integrated Defense Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics Life Cycle Management System, version 5.4, 15 June 2010. Created by the Defense Acquisition University. Available here.

These policies and bureaucracies have served to guide the award and development of some truly amazing programs and seem to have been the right tool for the environment and problem set of the 1980s. Without diving too deeply into the historical research, it seems that the result was a more efficient and streamlined competitive process that facilitated the development of many great systems, back in an era where it took 10-15 years to develop and field great systems.

Since the implementation of the CICA, FAR, and DFARS, the digital revolution happened. Engineering, test, and development cycles shortened drastically, and new types of commercial companies emerged and have supplanted many traditional defense-oriented organizations as the leaders of cutting-edge innovation in the United States. More pages and exceptions have been added to the old acquisition guidelines to try and accommodate new technologies, but the core issue is that the system that was designed for the pre-digital revolution economy has proven to be suboptimal for the reality in which we now find ourselves.

Alternative Approaches

This is not a new or unrecognized issue. General Mark Milley, the Chief of Staff of the Army, had a wonderful series of comments in response to having to use the acquisition system to buy a new pistol for the Army. “We’re not figuring out the next lunar landing. This is a pistol. Two years to test? At $17 million? You give me $17 million on a credit card, and I’ll call Cabela’s tonight, and I’ll outfit every Soldier, Sailor, Airman and Marine with a pistol for $17 million. And I’ll get a discount on a bulk buy.”Many alternative contract vehicles have also been created or energized in recent years to support faster acquisition processes for limited types of items. The Army’s Rapid Equipping Force (REF) is one example, designed to rapidly buy tools needed by soldiers in combat. There has also been an increase in the use of Other Transaction Authority (OTA) contracts, which are based on a legal statute that dates back to the space race and provide another example of a FAR workaround.

The Defense Innovation Unit Experimental is an entire organization dedicated to accelerating access to innovation for the nation’s service members. These organizations and workarounds are extremely important and needed, but they represent only a small fraction of the defense budget. The larger defense acquisition system needs to be modernized or adjusted so that it is used only for certain types of systems such as next-generation aircraft carriers and the like.

The Right Tool for the Job

There may well be categories of equipment where the 1980s era FAR and DFARS regulations and bureaucracies are needed and appropriate, but it is hard to imagine that those processes are needed for everything. My suspicion is that a top-to-bottom reimagining of acquisition processes and authorities would be most likely to lead to a positive outcome. However, even a more logical segmentation of processes by the type of equipment or service that is being procured would be beneficial. Applying the same acquisition process to a nuclear submarine and an Enterprise Resource Planning software implementation seems counterintuitive.Although not a defense program, the fiasco that was the initial launch of healthcare.gov provides a tangible example of the issue. Healthcare.gov was built via the traditional FAR process. Shortly after passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) generated requirements, went through the competitive process, and awarded a series of 5 contracts totaling $251 million to CGI Federal to build, test, and maintain the exchange, which quickly spiraled out of control.

Bloomberg’s analysis of a DHHS Inspector General Report demonstrate that there were ultimately 60 separate contracts totaling $799 million awarded by early 2014. In addition to CGI Federal’s $251 million, Quality Software Services was awarded $164.9 million in contracts, as were HP Enterprise Services ($77.6M), Terremark Federal Group ($48.9M), Accenture ($45M), IDL Solutions ($31.8M), DEDE ($25.6M), Lockheed Martin ($19.7M), The Mitre Corp. ($17.4M), Maricom Systems ($14.4M), Quality Tech. ($13.2M), Booz Allen Hamilton ($12.5M), and 21 other companies.

This is madness -- and it is the result of applying a pre-digital revolution process to a fundamentally digital asset such as a website. The traditional acquisition process involves writing down a specific list of every feature, user interface, bell, and whistle that the buyer wants in a product or service, then asking multiple vendors to submit bids to build it. At the core of this process is the idea that you can sit down and write out exactly what you are going to want, in many cases before that object, website, or service exists.

This is fine for buying a bullet that needs to be of specific dimensions and quality so that it can be fired from a weapon system. We can argue whether or not it works for something more complex, like a fighter aircraft. But it is simply not how software development works. Agile development, adaptive planning, and evolutionary design are the keys to successful software development in most cases, and are often at odds with the requirements-based acquisition process. One size does not fit all, and some of the tools that were developed prior to the digital revolution need to be reevaluated in context of the current environment.

Revisit the RFP and Set-Asides

The quintessential document of the FAR is the Request for Proposals (RFP). This is the document that establishes the definition of the good or service that the government wants to buy, and the rules under which bidders will be evaluated. It would be hard to imagine constructing a document that is less welcoming to the uninitiated and more likely to deter a “nontraditional defense contractor” from wanting to participate in a government program. The typical DoD RFP is around 150 pages, plus several attachments that total another 50-100 pages (the Army's new handgun RFP, for example, is 351 pages). Of the 150 pages in the base document, 85+% are pages and pages of byzantine certifications, representations, terms, and conditions, many of which reference other laws and government policy documents. These documents often look like they were scanned off a typewriter from the 1980s. The cover document looks like a form from the 1950s. It is completely intimidating, and can take hours for one who is not a government contracting professional to find the part that explains what they want to buy.In reality, the majority of an RFP is cut-and-paste from prior RFPs, and there are only several sections that really matter (sections C, L, M, and sometimes K for those wondering). I am unconvinced that most of the contract officers I’ve known fully understand all of the legal ramifications of the RFPs they publish, and 100+ pages of such ramifications how could they? If the DoD is serious about encouraging new companies to enter the government contracting space, these documents need a serious facelift and user-experience overhaul. They do not reflect the way that commercial business is done in the age of high-tech, and unsurprisingly they are primarily ignored by most leading-edge technology companies.

The small business set-asides are another factor in the RFP that may benefit from reevaluation. Set-asides are percentages of contract dollars that are reserved for different categories of “disadvantaged businesses”, such as women-owned, veteran-owned, service-disabled veteran-owned, historically black college or university / minority institutions, and HUBZone businesses. These are all well-intentioned programs that are designed to use federal dollars to create economic opportunities for different groups of people.

In practice, however, in many cases, they have become part of the game that companies play to win government business. Government buyers have certain targets for percentage of funds they need to spend with each set-aside group. Large companies build their small business subcontract plans to map to these targets, bringing in set-aside companies only to provide the least valuable, most commoditized parts of the contract -- which often ensures that the set-aside companies remain qualified only to do set-aside work in the government sector. Furthermore, set-asides also confuse non-traditional contractors and raise suspicion that these contracts are not truly being competitively awarded, even when they are. Confusion and suspicion are deterrents for many companies with other options for investing their time and resources.

If the goal of the defense acquisition process were to facilitate the economic prosperity of different segments of the American population as directed by Congress, then this system would be fine. If the goal is to provide the best goods and services for our military at the lowest cost in the most efficient way possible, then set-asides may benefit from being reevaluated along with the rest of the acquisition system.

Decentralize to Better Connect Users and Makers

In industry, the best companies tend to bring their product development teams close to their customers to ensure they build products that their customers want to use. If they fail to accomplish this, no one buys their products and they go out of business. In government, more often than not the acquisition process deliberately separates the users from the equipment manufacturers in the name of objectivity and process integrity. This is a bug in the acquisition system, not a feature.Users and makers of military equipment should be brought closer together, just as they are in the civilian world. This will allow for more user-centric design, better tools, and a greater understanding of product requirements and the challenges that operators face. It will also open the aperture for what is possible, as another problem inherent in the current system is that it forces acquisition professionals to write requirements explaining what they want in detail, when they often have only a limited understanding of what is possible.

Focus on Desired Outcomes, Not Tools

In a time of rapidly evolving capabilities and technologies, massive investments in large fixed platforms that can only be updated every 25-40 years may no longer be the most efficient way to achieve military objectives. There is a time and place for the aircraft carrier, tank, and nuclear submarine. However, if the military objective is to destroy ship-sized targets in the South China Sea, for example, a weaponized drone with a satellite-based targeting and communication system might be able to accomplish that mission at a fraction of the cost and risk. Furthermore, when countermeasures evolve as a result of new technology, the weapon system could be far more easily replaced with something that works in the new environment.This is admittedly not a tactically accurate example, but hopefully illustrates the point that there are other ways to think about military equipment in terms of desired effects, as opposed to the idea that we need to have better versions of the pre-digital revolution systems we have always had “just because”.

If, after deliberate and open-minded evaluation, defense professionals decide that these conventional systems are indeed the best tools to achieve the nation's desired outcomes, then so be it. However, I am suspect of anyone's ability to anticipate what a major weapons platform would need to do 23 years in the future (e.g. the F35 timeline) in this age of rapidly changing technology, and suggest that we need to rethink our requirements generation process along with our acquisition systems, and build in the capacity to evolve our tools more quickly.

Fail Fast and Adjust Quickly

Good organizations that are pushing the leading edge of technology and innovation sometimes fail. I suspect that organizations that never fail in R&D or product initiatives are not being aggressive enough with their development programs. The good organizations are able to recognize failure quickly, learn from it, and move on to other priorities.Failure in the defense acquisition business typically results in Congressional hearings and ruined careers. This is a hard balance to find, but along with decentralization we need to rethink the system of incentives and goals to incentivize defense technology teams to push the envelope and find the best possible tools to ensure the success of our armed forces in battle.

Trust Leaders

People are the heart of the armed forces. We put incredible trust in the judgment of young men and women in battle, where the worst-case scenario involves the loss of the most precious resource that we have: American lives. In the acquisition world there seems to be an attempt to replace judgment with process. To be certain, there is an element of process required to ensure scalable outcomes, but we have skewed the system too far towards process and away from trust and judgment. The balance must be regained.While 99+% of leaders who are empowered in this fashion will do the right thing, there will be leaders who break that trust. This is unfortunate and wasteful, but we should plan ahead to use those opportunities to purge the system and refine and improve our assessment and selection processes, as opposed to reverting to process. In the aggregate, the system will be better as a result of trusting in leaders and judgment, as opposed to relying primarily on process.

Reform Is a National Security Issue

To reiterate, acquisition reform is no longer just an issue for budget wonks, government contractors, and acquisition professionals. This is a national security issue, and the failure to innovate inside the Pentagon will have real life-and-death national security implications. The United States has the benefit of dozens of amazing models of innovation to look to in industry, from Silicon Valley and Austin to New York and Boston. Companies have been forced to reimagine their internal innovation processes by the forces of competition, and those that survive are far better for it.It is not anyone’s fault that a system designed in the 1980s needs to be overhauled, and the enormity of the current system will make the overhaul extremely difficult. Reform will take a long time, and will likely be messy. Fortunately, we have the resources, talent, and trained professionals who can build an efficient and long-overdue new system, given the time, trust, and mandate.